By Thurston Domina and Robert Wendell Eaves, Sr

Building a data-driven case for school desegregation

In August 2021, a research team that included scholars from the University of North Carolina School of Education, published findings that resulted from a research partnership with the Wake County Public School System (WCPSS) in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

The team’s findings, documented in The Kids on The Bus: The Academic Consequences of Diversity-Driven School Reassignments, support and add to the growing body of evidence that shows that school desegregation works. Federal efforts to enforce Brown vs. Board of Education and dismantle separate and unequal systems of public education improved Black children’s life trajectories, driving gains in educational achievement and attainment, increasing employment, and reducing arrests and crime victimization. Nonetheless, school desegregation efforts have consistently faced intense political resistance. Images of this resistance are seared in the nation’s memory: crowds of angry white protestors, spitting and jeering at the Little Rock Nine as they integrated Central High School; U.S. Marshals escorting nine-year-old Ruby Bridges into her New Orleans elementary school; battles between desegregation advocates and their opponents in the streets of 1970s Boston.

Opposition to desegregation efforts is no relic of the past; this backlash continues to the present day as illustrated by recent dispatches from San Francisco, New York City, Maryland’s Montgomery County, and North Carolina’s Charlotte-Mecklenburg County. As districts around the U.S. grapple with high levels of racial and socioeconomic segregation, and the Biden administration prepares to make a $100 million bet on a new generation of school desegregation efforts, researchers from the UNC School of Education forged a research-practice partnership with North Carolina’s Wake County Public School System (WCPSS) to explore the consequences of diversity-driven reassignments.

Looking back at Wake County Public School System results

Between 2000 and 2010, WCPSS implemented an innovative set of policies, including the “40/25” rule, which declared that no school’s enrollment should exceed 40 percent socioeconomically disadvantaged students or 25 percent below grade-level students. It sought to accomplish this with a “controlled choice” approach that gave parents opportunities to choose their children’s schools while allowing the district to manage the assignment process in ways that served its desegregation goals. The district was divided into geographic nodes containing roughly 150 students each, with each node assigned to a “base” elementary, middle and high school.

While families had a menu of school choices, their node’s “base” school served as their default school of attendance. To maintain socioeconomic and achievement balance, WCPSS annually reassigned several nodes—and the students residing in them—to different base schools, generally reassigning relatively high-poverty residential nodes to lower-poverty base schools and vice versa.

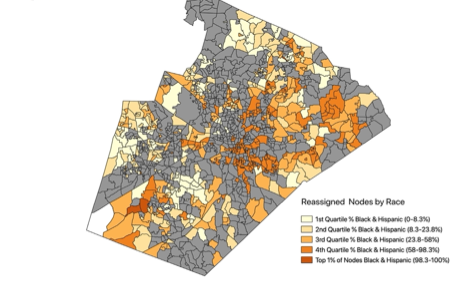

More than 20 percent of students enrolled in WCPSS experienced one or more reassignments under the policy during the decade in which it was in place. Figure 1 features a map of WCPSS’s residential nodes, shading reassigned nodes according to their concentration of students of color.

As the map illustrates, reassignments affected students across the district, including Black, white and Hispanic students.

While the district broadly discontinued these policies in 2010, WCPSS leadership remains committed to school diversity. As such, district officials worked closely with the research team to retrieve and assemble annual records for each student who attended WCPSS between the 1999-2000 and 2010-11 academic years. These records provide information on students’ residential location, school assignment, enrollment decisions and academic performance. Data were used to compare outcomes for students whose nodes were reassigned to outcomes for otherwise similar students whose nodes were not reassigned. The research team examined students’ subsequent test scores, attendance records and disciplinary records.

The team’s analyses yield three main conclusions:

First, although WCPSS’s policy allowed families to opt out of their newly reassigned schools, most reassigned students ultimately attended these schools. This finding is important because it suggests that districts can create more diverse and inclusive school assignment boundaries even with policies that allow a considerable degree of school choice.

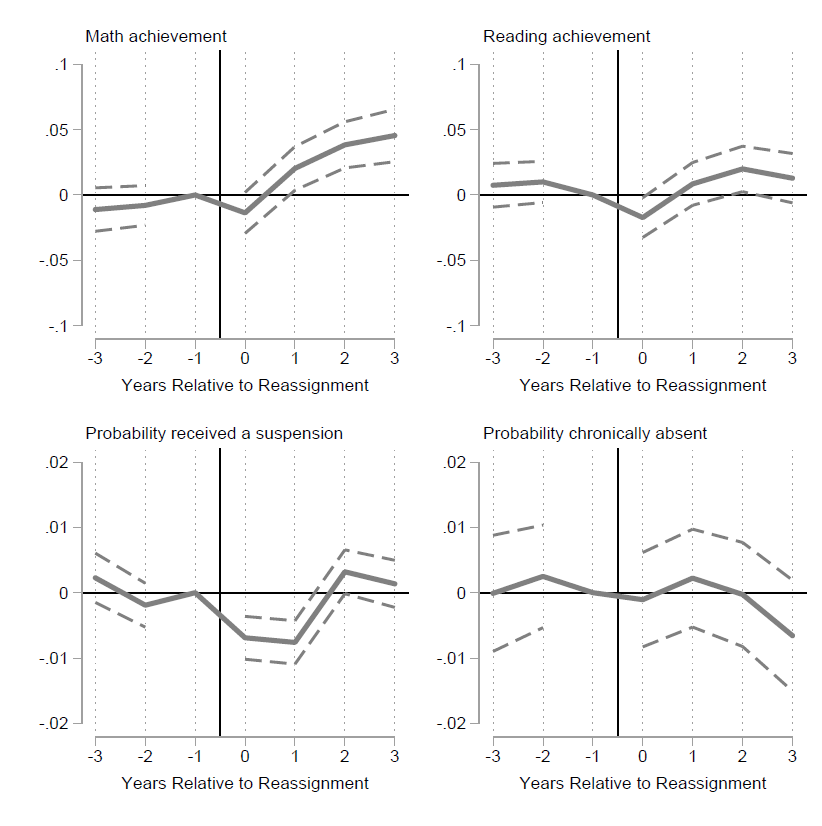

Second, despite widespread concerns about the potential harms of “busing” to achieve diversity goals, the researchers found no meaningful evidence of negative consequences of reassignment for reassigned students. Indeed, as the findings reported in Figure 2 illustrate, the analyses indicate that reassignment had modest positive effects on reassigned students’ math achievement, in the range of 0.02-0.04 standard deviations. Additionally, reassigned students’ rates of suspension dropped by about one percentage point in the year of reassignment and the subsequent year, a decline of 20 percent off the base suspension rate. These findings indicate that—in this case at least—concerns about the academic and social costs of school reassignment are unfounded. Carefully designed and implemented school assignment policies like the one WCPSS implemented in the early 2000s can improve school diversity without imposing academic or disciplinary costs on reassigned students. Additional analyses indicate that the benefits associated with reassignment were relatively widespread and found no evidence to suggest that academic outcomes declined for students initially enrolled in low-poverty schools after reassignment.

Third, the study shows that students who do and do not attend their base school have similar outcome trajectories post-reassignment. The team is reluctant to draw firm causal conclusions based on this finding. Nonetheless, it suggests that students benefit from reassignment whether they attend their new base schools or transfer to a choice school.

Looking Ahead—In Wake County and Beyond

As trends toward socioeconomic segregation across public schools intensify across the U.S. and the COVID pandemic sheds light on deep and persistent inequalities in public schools, the research team believes now is the time for educational policymakers to undertake brave and ambitious new approaches to school desegregation. WCPSS’s 2000-2010 socioeconomic reassignment policy can be a touchstone in this policy conversation, potentially emboldening equity-oriented policymakers in Wake County and around the U.S. This policy framework—which has attracted considerable academic attention over the years—was neither perfect nor uncontroversial. In fact, voter backlash to the policy led to the election of an anti-desegregation slate of school board candidates in 2009. Those who want to examine additional analysis can review the following articles:

- The Life and Death of Desegregation Policy in Wake County Public School System and Charlotte-Mecklenberg Schools

- Can Class-Based Substitute for Race-Based Student Assignment Plans? Evidence from Wake County, North Carolina

- Socioeconomic-Based School Assignment Policy and Racial Segregation Levels: Evidence from the Wake County Public School System

Today, as the WCPSS district confronts rising levels of racial and socioeconomic school segregation, researchers continue working with district leaders as they develop new approaches to use school assignments to boost diversity. By building on the WCPSS model, policymakers can realize the profound benefits of educational diversity, even in an era when courts subject racially sensitive desegregation efforts to sharp scrutiny and school choice plans provide new opportunities for students to avoid socioeconomically diverse schools. Contrary to widespread worries about the costs of desegregation, the analysis of this study suggests that educational policymakers can realize these benefits while simultaneously enriching the educational experiences of reassigned students.